Hospitals are large, complex clinical environments that present many problems during design and construction. Engaging engineers – the world’s great problem solvers – early can identify problems, risks and opportunities, says Stantec’s Matthew Quin and Grant Sheppard. Here’s how…

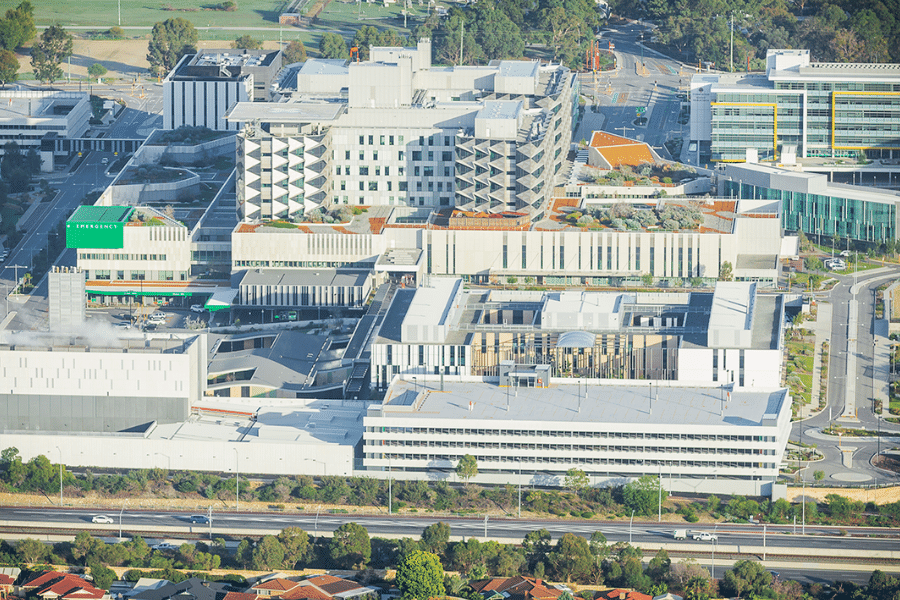

Multi-billion-dollar hospital projects are capturing headlines and headspace around Australia. Over the course of 2022 alone, the Victorian Government has promised to deliver around $6 billion in hospital infrastructure projects, the Queensland Government has allocated $9.78 billion in new hospital funding over the next six years and the WA Government has confirmed the site for a new $1.8 billion women’s and babies hospital in Perth.

Quin and Sheppard are both principals and senior electrical project engineers with Stantec. Together they have delivered many large complex healthcare projects.

“We are sometimes handed a set of drawings – long after the business cases and concept planning has been completed – and can see problems immediately,” says Quin.

“It may be that the hospital will be constructed over existing high voltage services, or that the energy needs are inadequate if the building will be electrified,” he says, referring to the replacement of gas supplied appliances with electric ones.

“It might be that the spaces allocated for the communications enclosures are too small, or one of countless other challenges. All these problems can be avoided entirely with early engineering input.”

Take the technical complexity of meeting the regulatory requirement for backup power. Every Australian hospital providing critical care services must have emergency backup power to guarantee that there is minimal disruption to lifesaving medical equipment in the event of a power failure.

“At the very early stage of planning, the client and architect often draw a box to indicate space for plant. It’s reasonable on the surface — but generators don’t just take up a lot of space. They also vibrate and make a lot of noise. A few floors above or below, surgeons might be expected to carry out delicate surgery,” Quin explains.

One hospital proposal “significantly changed” because the position of the generator on the roof of the hospital proved unviable. “A generator lasts approximately 30 years. The crane that would be needed to remove and replace the generator at end of life would need to be placed within the emergency department drop-off zone.” The central energy plant in another small regional healthcare facility was elevated around 3.5 metres above the 100-year flood level to safeguard the continued operation of the hospital’s critical services in the event of flooding.

Another intensive care area which went through concept planning and business case stages without engineering input, was located directly above a high voltage substation, causing headaches for Stantec’s engineering team, Quin adds. Transformers, switchboards, power lines, mobile phone towers and similar transmitters all generate electromagnetic fields. “There are concerns that electromagnetic fields can influence sensitive medical equipment and patients. To counteract the electromagnetic fields the floor had to be lined with lead sheeting.”

“Rapidly advancing technology – from 5G to WiFi, robotics to tagging systems, CCTV to real-time locating systems – are improving outcomes for patients across the world. However, these have space and energy efficiency implications as well which must be considered in the design,” Sheppard notes.

“Hospitals are data-hungry and getting data-hungrier each year. Clients are often surprised how much space they must allocate to communications rooms to meet this rising demand for ‘Internet of Things’ (IoT) technologies. It’s not just a small cupboard on each floor anymore.

“The continuing trend is for smart devices to receive power over the communications lines – called ‘Power over Ethernet’ (PoE) – and the amount of power being delivered in this way increases with every new version. Couple this with the rollout of 5G in-building systems (DAS), this generates significant heat in the communications room, which we need to address with purpose-designed air-conditioning solutions.”

Electrification of hospitals is another example where engineers turn Green Star aspiration into actual outcomes. Several large hospitals – notably South Australia’s new $685 million Women’s and Children’s Hospital – will operate without input from the gas network.

“Meeting Green Star requirements isn’t simply a matter of switching gas boilers to electric ones,” Quin says. “Electric boilers use significantly more electricity, and as the electrical load increases, transformers, generators and switchboard get bigger.” He points to one proposal, where the sudden late inclusion of electrification required a substantial redesign of the energy plant, “which delayed the project by several months and came with cost implications”.

“Interfacing a new hospital extension with old infrastructure brings other complexities”, Sheppard adds. “How will clinical operations be maintained during construction? In many cases, the cost of closing a section of the hospital can have cost impacts. ”Engineers are natural problem-solvers. “But we need to be in place to solve the problems early-on in the project lifecycle — or preferably, before they happen,” Quin and Sheppard agree.

“Engage the engineering team early. With the right engineering experts, hospital projects don’t just avoid costly mistakes; they also help to define and unify the vision,” Quin concludes.

Stantec has been a leader in healthcare planning and design for more than five decades. Find out how Stantec is putting its clients at the forefront of best practice, technology innovation, and high-performance healthcare delivery.